Proprietary Surveillance

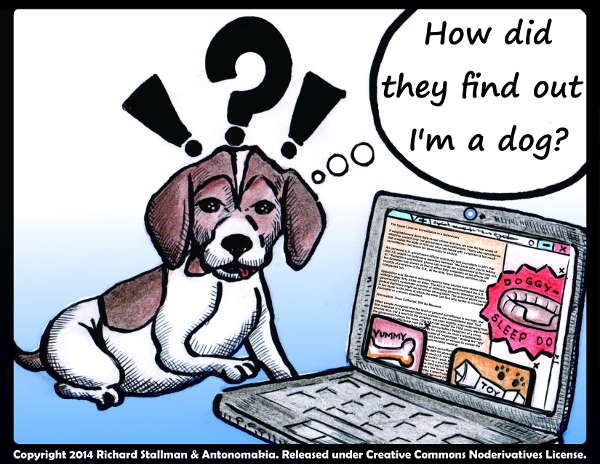

Nonfree (proprietary) software is very often malware (designed to mistreat the user). Nonfree software is controlled by its developers, which puts them in a position of power over the users; that is the basic injustice. The developers and manufacturers often exercise that power to the detriment of the users they ought to serve.

This typically takes the form of malicious functionalities.

A common malicious functionality is to snoop on the user. This page records clearly established cases of proprietary software that spies on or tracks users. Manufacturers even refuse to say whether they snoop on users for the state.

All appliances and applications that are tethered to a specific server are snoopers by nature. We do not list them here because they have their own page: Proprietary Tethers.

There is a similar site named Spyware Watchdog that classifies spyware programs, so that users can be more aware that they are installing spyware.

If you know of an example that ought to be in this page but isn't here, please write to <[email protected]> to inform us. Please include the URL of a trustworthy reference or two to serve as specific substantiation.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Spyware in Laptops and Desktops

Spyware on Mobiles

Spyware in Applications

Spyware in Connected Equipment

Spyware on the Web

Spyware in Networks

Introduction

For decades, the Free Software movement has been denouncing the abusive surveillance machine of proprietary software companies such as Microsoft and Apple. In the recent years, this tendency to watch people has spread across industries, not only in the software business, but also in the hardware. Moreover, it also spread dramatically away from the keyboard, in the mobile computing industry, in the office, at home, in transportation systems, and in the classroom.

Aggregate or anonymized data

Many companies, in their privacy policy, have a clause that claims they share aggregate, non-personally identifiable information with third parties/partners. Such claims are worthless, for several reasons:

- They could change the policy at any time.

- They can twist the words by distributing an “aggregate” of “anonymized” data which can be reidentified and attributed to individuals.

- The raw data they don't normally distribute can be taken by data breaches.

- The raw data they don't normally distribute can be taken by subpoena.

Therefore, we must not be distracted by companies' statements of what they will do with the data they collect. The wrong is that they collect it at all.

Latest additions

Entries in each category are in reverse chronological order, based on the dates of publication of linked articles. The latest additions are listed on the main page of the Malware section.

Spyware in Laptops and Desktops

(#OSSpyware)Windows

(#SpywareInWindows)-

2023-02

As soon as it boots, and without asking any permission, Windows 11 starts to send data to online servers. The user's personal details, location or hardware information are reported to Microsoft and other companies to be used as telemetry data. All of this is done is the background, and users have no easy way to prevent it—unless they switch the computer offline.

-

2023-01

Microsoft released an “update” that installs a surveillance program on users' computers to gather data on some installed programs for Microsoft's benefit. The update is rolling out automatically, and the program runs “one time silently.”

-

2022-09

Windows 11 Home and Pro now require internet connection and a Microsoft account to complete the installation. Windows 11 Pro had an option to create a local account instead, but the option has been removed. This account can (and most certainly will) be used for surveillance and privacy violations. Thankfully, a free software tool named Rufus can bypass those requirements, or help users install a free operating system instead.

-

2019-12

Microsoft is tricking users to create an account on their network to be able to install and use the Windows operating system, which is malware. The account can be used for surveillance and/or violating people's rights in many ways, such as turning their purchased software to a subscription product.

-

2017-12

HP's proprietary operating system includes a proprietary keyboard driver with a key logger in it.

-

2017-10

Windows 10 telemetry program sends information to Microsoft about the user's computer and their use of the computer.

Furthermore, for users who installed the fourth stable build of Windows 10, called the “Creators Update,” Windows maximized the surveillance by force setting the telemetry mode to “Full”.

The “Full” telemetry mode allows Microsoft Windows engineers to access, among other things, registry keys which can contain sensitive information like administrator's login password.

-

2017-02

DRM-restricted files can be used to identify people browsing through Tor. The vulnerability exists only if you use Windows.

-

2016-11

By default, Windows 10 sends debugging information to Microsoft, including core dumps. Microsoft now distributes them to another company.

-

2016-08

In order to increase Windows 10's install base, Microsoft blatantly disregards user choice and privacy.

-

2016-03

Windows 10 comes with 13 screens of snooping options, all enabled by default, and turning them off would be daunting to most users.

-

2016-01

It appears Windows 10 sends data to Microsoft about what applications are running.

-

2015-12

Microsoft has backdoored its disk encryption.

-

2015-11

A downgrade to Windows 10 deleted surveillance-detection applications. Then another downgrade inserted a general spying program. Users noticed this and complained, so Microsoft renamed it to give users the impression it was gone.

To use proprietary software is to invite such treatment.

-

2015-08

Intel devices will be able to listen for speech all the time, even when “off.”

-

2015-08

Windows 10 sends identifiable information to Microsoft, even if a user turns off its Bing search and Cortana features, and activates the privacy-protection settings.

-

2015-07

Windows 10 ships with default settings that show no regard for the privacy of its users, giving Microsoft the “right” to snoop on the users' files, text input, voice input, location info, contacts, calendar records and web browsing history, as well as automatically connecting the machines to open hotspots and showing targeted ads.

We can suppose Microsoft looks at users' files for the US government on demand, though the “privacy policy” does not explicitly say so. Will it look at users' files for the Chinese government on demand?

-

2015-06

Microsoft uses Windows 10's “privacy policy” to overtly impose a “right” to look at users' files at any time. Windows 10 full disk encryption gives Microsoft a key.

Thus, Windows is overt malware in regard to surveillance, as in other issues.

The unique “advertising ID” for each user enables other companies to track the browsing of each specific user.

It's as if Microsoft has deliberately chosen to make Windows 10 maximally evil on every dimension; to make a grab for total power over anyone that doesn't drop Windows now.

-

2014-10

It only gets worse with time. Windows 10 requires users to give permission for total snooping, including their files, their commands, their text input, and their voice input.

-

2014-05

Microsoft SkyDrive allows the NSA to directly examine users' data.

- 2014-01

-

2013-07

Spyware in older versions of Windows: Windows Update snoops on the user. Windows 8.1 snoops on local searches. And there's a secret NSA key in Windows, whose functions we don't know.

Microsoft's snooping on users did not start with Windows 10. There's a lot more Microsoft malware.

MacOS

(#SpywareInMacOS)-

2020-11

Apple has implemented a malware in its computers that imposes surveillance on users and reports users' computing to Apple.

The reports are even unencrypted and they've been leaking this data for two years already. This malware is reporting to Apple what user opens what program at what time. It also gives Apple power to sabotage users' computing.

-

2018-09

Adware Doctor, an ad blocker for MacOS, reports the user's browsing history.

-

2014-11

Apple has made various MacOS programs send files to Apple servers without asking permission. This exposes the files to Big Brother and perhaps to other snoops.

It also demonstrates how you can't trust proprietary software, because even if today's version doesn't have a malicious functionality, tomorrow's version might add it. The developer won't remove the malfeature unless many users push back hard, and the users can't remove it themselves.

-

2014-10

MacOS automatically sends to Apple servers unsaved documents being edited. The things you have not decided to save are even more sensitive than the things you have stored in files.

-

2014-10

Apple admits the spying in a search facility, but there's a lot more snooping that Apple has not talked about.

-

2014-10

Various operations in the latest MacOS send reports to Apple servers.

-

2014-01

Spotlight search sends users' search terms to Apple.

There's a lot more iThing spyware, and Apple malware.

BIOS

(#SpywareInBIOS)-

2015-09

Lenovo stealthily installed crapware and spyware via BIOS on Windows installs. Note that the specific sabotage method Lenovo used did not affect GNU/Linux; also, a “clean” Windows install is not really clean since Microsoft puts in its own malware.

Spyware on Mobiles

(#SpywareOnMobiles)All “Smart” Phones

(#SpywareInTelephones)-

2021-06

El Salvador Dictatorship's Chivo wallet is spyware, it's a proprietary program that breaks users' freedom and spies on people; demands personal data such as the national ID number and does face recognition, and it is bad security for its data. It also asks for almost every malware permission in people's smartphones.

The article criticizes it for faults in “data protection”, though “data protection” is the wrong approach to privacy anyway.

-

2021-06

Almost all proprietary health apps harvest users' data, including sensitive health information, tracking identifiers, and cookies to track user activities. Some of these applications are tracking users across different platforms.

-

2021-01

As of 2021, WhatsApp (one of Facebook's subsidiaries) is forcing its users to hand over sensitive personal data to its parent company. This increases Facebook's power over users, and further jeopardizes people's privacy and security.

Instead of WhatsApp you can use GNU Jami, which is free software and will not collect your data.

-

2020-06

Most apps are malware, but Trump's campaign app, like Modi's campaign app, is especially nasty malware, helping companies snoop on users as well as snooping on them itself.

The article says that Biden's app has a less manipulative overall approach, but that does not tell us whether it has functionalities we consider malicious, such as sending data the user has not explicitly asked to send.

-

2018-09

Tiny Lab Productions, along with online ad businesses run by Google, Twitter and three other companies are facing a lawsuit for violating people's privacy by collecting their data from mobile games and handing over these data to other companies/advertisers.

-

2016-01

The natural extension of monitoring people through “their” phones is proprietary software to make sure they can't “fool” the monitoring.

-

2015-10

According to Edward Snowden, agencies can take over smartphones by sending hidden text messages which enable them to turn the phones on and off, listen to the microphone, retrieve geo-location data from the GPS, take photographs, read text messages, read call, location and web browsing history, and read the contact list. This malware is designed to disguise itself from investigation.

-

2013-11

The NSA can tap data in smart phones, including iPhones, Android, and BlackBerry. While there is not much detail here, it seems that this does not operate via the universal back door that we know nearly all portable phones have. It may involve exploiting various bugs. There are lots of bugs in the phones' radio software.

-

2013-07

Portable phones with GPS will send their GPS location on remote command, and users cannot stop them. (The US says it will eventually require all new portable phones to have GPS.)

iThings

(#SpywareIniThings)-

2022-11

The iMonster app store client programs collect many kinds of data about the user's actions and private communications. “Do not track” options are available, but tracking doesn't stop if the user activates them: Apple keeps on collecting data for itself, although it claims not to send it to third parties.

Apple is being sued for that.

-

2021-05

Apple is moving its Chinese customers' iCloud data to a datacenter controlled by the Chinese government. Apple is already storing the encryption keys on these servers, obeying Chinese authority, making all Chinese user data available to the government.

-

2020-09

Facebook snoops on Instagram users by surreptitously turning on the device's camera.

-

2020-04

Apple whistleblower Thomas Le Bonniec reports that Apple made a practice of surreptitiously activating the Siri software to record users' conversations when they had not activated Siri. This was not just occasional, it was systematic practice.

His job was to listen to these recordings, in a group that made transcripts of them. He does not believes that Apple has ceased this practice.

The only reliable way to prevent this is, for the program that controls access to the microphone to decide when the user has “activated” any service, to be free software, and the operating system under it free as well. This way, users could make sure Apple can't listen to them.

-

2019-10

Safari occasionally sends browsing data from Apple devices in China to the Tencent Safe Browsing service, to check URLs that possibly correspond to “fraudulent” websites. Since Tencent collaborates with the Chinese government, its Safe Browsing black list most certainly contains the websites of political opponents. By linking the requests originating from single IP addresses, the government can identify dissenters in China and Hong Kong, thus endangering their lives.

-

2019-05

In spite of Apple's supposed commitment to privacy, iPhone apps contain trackers that are busy at night sending users' personal information to third parties.

The article mentions specific examples: Microsoft OneDrive, Intuit's Mint, Nike, Spotify, The Washington Post, The Weather Channel (owned by IBM), the crime-alert service Citizen, Yelp and DoorDash. But it is likely that most nonfree apps contain trackers. Some of these send personally identifying data such as phone fingerprint, exact location, email address, phone number or even delivery address (in the case of DoorDash). Once this information is collected by the company, there is no telling what it will be used for.

-

2017-11

The DMCA and the EU Copyright Directive make it illegal to study how iOS cr…apps spy on users, because this would require circumventing the iOS DRM.

-

2017-09

In the latest iThings system, “turning off” WiFi and Bluetooth the obvious way doesn't really turn them off. A more advanced way really does turn them off—only until 5am. That's Apple for you—“We know you want to be spied on”.

-

2017-02

Apple proposes a fingerprint-scanning touch screen—which would mean no way to use it without having your fingerprints taken. Users would have no way to tell whether the phone is snooping on them.

-

2016-11

iPhones send lots of personal data to Apple's servers. Big Brother can get them from there.

-

2016-09

The iMessage app on iThings tells a server every phone number that the user types into it; the server records these numbers for at least 30 days.

-

2015-09

iThings automatically upload to Apple's servers all the photos and videos they make.

iCloud Photo Library stores every photo and video you take, and keeps them up to date on all your devices. Any edits you make are automatically updated everywhere. […]

(From Apple's iCloud information as accessed on 24 Sep 2015.) The iCloud feature is activated by the startup of iOS. The term “cloud” means “please don't ask where.”

There is a way to deactivate iCloud, but it's active by default so it still counts as a surveillance functionality.

Unknown people apparently took advantage of this to get nude photos of many celebrities. They needed to break Apple's security to get at them, but NSA can access any of them through PRISM.

-

2014-09

Apple can, and regularly does, remotely extract some data from iPhones for the state.

This may have improved with iOS 8 security improvements; but not as much as Apple claims.

-

2014-07

Several “features” of iOS seem to exist for no possible purpose other than surveillance. Here is the Technical presentation.

-

2014-01

The iBeacon lets stores determine exactly where the iThing is, and get other info too.

-

2013-12

Either Apple helps the NSA snoop on all the data in an iThing, or it is totally incompetent.

-

2013-08

The iThing also tells Apple its geolocation by default, though that can be turned off.

-

2012-10

There is also a feature for web sites to track users, which is enabled by default. (That article talks about iOS 6, but it is still true in iOS 7.)

-

2012-04

Users cannot make an Apple ID (necessary to install even gratis apps) without giving a valid email address and receiving the verification code Apple sends to it.

Android Telephones

(#SpywareInAndroid)-

2020-12

Baidu apps were caught collecting sensitive personal data that can be used for lifetime tracking of users, and putting them in danger. More than 1.4 billion people worldwide are affected by these proprietary apps, and users' privacy is jeopardized by this surveillance tool. Data collected by Baidu may be handed over to the Chinese government, possibly putting Chinese people in danger.

-

2020-10

Samsung is forcing its smartphone users in Hong Kong (and Macau) to use a public DNS in Mainland China, using software update released in September 2020, which causes many unease and privacy concerns.

-

2020-04

Xiaomi phones report many actions the user takes: starting an app, looking at a folder, visiting a website, listening to a song. They send device identifying information too.

Other nonfree programs snoop too. For instance, Spotify and other streaming dis-services make a dossier about each user, and they make users identify themselves to pay. Out, out, damned Spotify!

Forbes exonerates the same wrongs when the culprits are not Chinese, but we condemn this no matter who does it.

-

2018-12

Facebook's app got “consent” to upload call logs automatically from Android phones while disguising what the “consent” was for.

-

2018-11

An Android phone was observed to track location even while in airplane mode. It didn't send the location data while in airplane mode. Instead, it saved up the data, and sent them all later.

-

2017-11

Android tracks location for Google even when “location services” are turned off, even when the phone has no SIM card.

-

2016-11

Some portable phones are sold with spyware sending lots of data to China.

-

2016-09

Google Play (a component of Android) tracks the users' movements without their permission.

Even if you disable Google Maps and location tracking, you must disable Google Play itself to completely stop the tracking. This is yet another example of nonfree software pretending to obey the user, when it's actually doing something else. Such a thing would be almost unthinkable with free software.

-

2015-07

Samsung phones come with apps that users can't delete, and they send so much data that their transmission is a substantial expense for users. Said transmission, not wanted or requested by the user, clearly must constitute spying of some kind.

-

2014-03

Samsung's back door provides access to any file on the system.

-

2013-08

Spyware in Android phones (and Windows? laptops): The Wall Street Journal (in an article blocked from us by a paywall) reports that the FBI can remotely activate the GPS and microphone in Android phones and laptops (presumably Windows laptops). Here is more info.

-

2013-07

Spyware is present in some Android devices when they are sold. Some Motorola phones, made when this company was owned by Google, use a modified version of Android that sends personal data to Motorola.

-

2013-07

A Motorola phone listens for voice all the time.

-

2013-02

Google Play intentionally sends app developers the personal details of users that install the app.

Merely asking the “consent” of users is not enough to legitimize actions like this. At this point, most users have stopped reading the “Terms and Conditions” that spell out what they are “consenting” to. Google should clearly and honestly identify the information it collects on users, instead of hiding it in an obscurely worded EULA.

However, to truly protect people's privacy, we must prevent Google and other companies from getting this personal information in the first place!

-

2011-11

Some manufacturers add a hidden general surveillance package such as Carrier IQ.

E-Readers

(#SpywareInElectronicReaders)-

2016-03

E-books can contain JavaScript code, and sometimes this code snoops on readers.

-

2014-10

Adobe made “Digital Editions,” the e-reader used by most US libraries, send lots of data to Adobe. Adobe's “excuse”: it's needed to check DRM!

-

2012-12

Spyware in many e-readers—not only the Kindle: they report even which page the user reads at what time.

Spyware in Applications

(#SpywareInApplications)-

2023-06

Edge sends the URLs of images the user views to Microsoft's servers by default, supposedly to “enhance” them. And these images may end up on the NSA's servers.

Microsoft claims its nonfree browser sends the URLs without identifying you, which cannot be true, since at least your IP address is known to the server if you don't take extra measures. Either way, such enhancer service is unjust because any image editing should be done on your own computer using installed free software.

The article describes how to disable sending the URLs. That makes a change for the better, but we suggest that you instead switch to a freedom-respecting browser with additional privacy features such as IceCat.

-

2023-05

Some employers are forcing employees to run “monitoring software” on their computers. These extremely intrusive proprietary programs can take screenshots at regular intervals, log keystrokes, record audio and video, etc. Such practices have been shown to deteriorate employees' well-being, and trade unions in the European union have voiced their concerns about them. The requirement for employee's consent, which exists in some countries, is a sham because most often the employee is not free to refuse. In short, these practices should be abolished.

-

2022-05

A worldwide investigation found that most of the applications that school districts recommended for remote education during the COVID-19 pandemic track and collect personal data from children as young as below the age of five. These applications, and their websites, send the collected information to ad giants such as Facebook and Google, and they are still being used in the classrooms even after some of the schools reopened.

-

2018-05

The Verify browser extension by Storyful spies on the reporters that use it.

Desktop Apps

(#SpywareInDesktopApps)-

2020-11

Microsoft's Office 365 suite enables employers to snoop on each employee. After a public outburst, Microsoft stated that it would remove this capability. Let's hope so.

-

2019-12

Some Avast and AVG extensions for Firefox and Chrome were found to snoop on users' detailed browsing habits. Mozilla and Google removed the problematic extensions from their stores, but this shows once more how unsafe nonfree software can be. Tools that are supposed to protect a proprietary system are, instead, infecting it with additional malware (the system itself being the original malware).

-

2019-04

As of April 2019, it is no longer possible to disable an unscrupulous tracking anti-feature that reports users when they follow ping links in Apple Safari, Google Chrome, Opera, Microsoft Edge and also in the upcoming Microsoft Edge that is going to be based on Chromium.

-

2018-11

Foundry's graphics software reports information to identify who is running it. The result is often a legal threat demanding a lot of money.

The fact that this is used for repression of forbidden sharing makes it even more vicious.

This illustrates that making unauthorized copies of nonfree software is not a cure for the injustice of nonfree software. It may avoid paying for the nasty thing, but cannot make it less nasty.

Mobile Apps

(#SpywareInMobileApps)-

2023-08

The Yandex company has started to give away Yango taxi ride data to Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB). The Russian government (and whoever else receives the the data) thus has access to a wealth of personal information, including who traveled where, when, and with which driver. Yandex claims that it complies with European regulations for data collected in the European Economic Area, Switzerland or Israel. But what about the rest of the world?

-

2023-04

The Pinduoduo app snoops on other apps, and takes control of them. It also installs additional malware that is hard to remove.

-

2022-06

Canada has fined the company Tim Hortons for making an app that tracks people's movements to learn things such as where they live, where they work, and when they visit competitors' stores.

-

2022-04

New Amazon worker chat app would ban specific words Amazon doesn't like, such as “union”, “restrooms”, and “pay raise”. If the app was free, workers could modify the program so it acts as they wish, not how Amazon wants it.

-

2022-03

The nonfree app “Along,” developed by a company controlled by Zuckerberg, leads students to reveal to their teacher personal information about themselves and their families. Conversations are recorded and the collected data sent to the company, which grants itself the right to sell it. See also Educational Malware App “Along”.

-

2022-01

The data broker X-Mode bought location data about 20,000 people collected by around 100 different malicious apps.

-

2021-11

A building in LA, with a supermarket in it, demands customers load a particular app to pay for parking in the parking lot, and accept pervasive surveillance. They also have the option of entering their license plate numbers in a kiosk. That is an injustice, too.

-

2021-06

TikTok apps collect biometric identifiers and biometric information from users' smartphones. The company behind it does whatever it wants and collects whatever data it can.

-

2021-04

The WeddingWire app saves people's wedding photos forever and hands over data to others, giving users no control over their personal information/data. The app also sometimes shows old photos and memories to users, without giving them any control over this either.

-

2021-02

The proprietary program Clubhouse is malware and a privacy disaster. Clubhouse collects people's personal data such as recordings of people's conversations, and, as a secondary problem, does not encrypt them, which shows a bad security part of the issue.

A user's unique Clubhouse ID number and chatroom ID are transmitted in plaintext, and Agora (the company behind the app) would likely have access to users' raw audio, potentially providing access to the Chinese government.

Even with good security of data transmission, collecting personal data of people is wrong and a violation of people's privacy rights.

-

2021-02

Many cr…apps, developed by various companies for various organizations, do location tracking unknown to those companies and those organizations. It's actually some widely used libraries that do the tracking.

What's unusual here is that proprietary software developer A tricks proprietary software developers B1 … B50 into making platforms for A to mistreat the end user.

-

2020-03

The Apple iOS version of Zoom is sending users' data to Facebook even if the user doesn't have a Facebook account. According to the article, Zoom and Facebook don't even mention this surveillance on their privacy policy page, making this an obvious violation of people's privacy even in their own terms.

-

2020-03

The Alipay Health Code app estimates whether the user has Covid-19 and tells the cops directly.

-

2020-01

The Amazon Ring app does surveillance for other companies as well as for Amazon.

-

2019-12

The ToToc messaging app seems to be a spying tool for the government of the United Arab Emirates. Any nonfree program could be doing this, and that is a good reason to use free software instead.

Note: this article uses the word “free” in the sense of “gratis.”

-

2019-12

iMonsters and Android phones, when used for work, give employers powerful snooping and sabotage capabilities if they install their own software on the device. Many employers demand to do this. For the employee, this is simply nonfree software, as fundamentally unjust and as dangerous as any other nonfree software.

-

2019-10

The Chinese Communist Party's “Study the Great Nation” app requires users to grant it access to the phone's microphone, photos, text messages, contacts, and internet history, and the Android version was found to contain a back-door allowing developers to run any code they wish in the users' phone, as “superusers.” Downloading and using this app is mandatory at some workplaces.

Note: The Washington Post version of the article (partly obfuscated, but readable after copy-pasting in a text editor) includes a clarification saying that the tests were only performed on the Android version of the app, and that, according to Apple, “this kind of ‘superuser’ surveillance could not be conducted on Apple's operating system.”

-

2019-09

The Facebook app tracks users even when it is turned off, after tricking them into giving the app broad permissions in order to use one of its functionalities.

-

2019-09

Some nonfree period-tracking apps including MIA Fem and Maya send intimate details of users' lives to Facebook.

-

2019-09

Keeping track of who downloads a proprietary program is a form of surveillance. There is a proprietary program for adjusting a certain telescopic rifle sight. A US prosecutor has demanded the list of all the 10,000 or more people who have installed it.

With a free program there would not be a list of who has installed it.

-

2019-07

Many unscrupulous mobile-app developers keep finding ways to bypass user's settings, regulations, and privacy-enhancing features of the operating system, in order to gather as much private data as they possibly can.

Thus, we can't trust rules against spying. What we can trust is having control over the software we run.

-

2019-07

Many Android apps can track users' movements even when the user says not to allow them access to locations.

This involves an apparently unintentional weakness in Android, exploited intentionally by malicious apps.

-

2019-05

The Femm “fertility” app is secretly a tool for propaganda by natalist Christians. It spreads distrust for contraception.

It snoops on users, too, as you must expect from nonfree programs.

-

2019-05

BlizzCon 2019 imposed a requirement to run a proprietary phone app to be allowed into the event.

This app is a spyware that can snoop on a lot of sensitive data, including user's location and contact list, and has near-complete control over the phone.

-

2019-04

Data collected by menstrual and pregnancy monitoring apps is often available to employers and insurance companies. Even though the data is “anonymized and aggregated,” it can easily be traced back to the woman who uses the app.

This has harmful implications for women's rights to equal employment and freedom to make their own pregnancy choices. Don't use these apps, even if someone offers you a reward to do so. A free-software app that does more or less the same thing without spying on you is available from F-Droid, and a new one is being developed.

-

2019-04

Google tracks the movements of Android phones and iPhones running Google apps, and sometimes saves the data for years.

Nonfree software in the phone has to be responsible for sending the location data to Google.

-

2019-03

Many Android phones come with a huge number of preinstalled nonfree apps that have access to sensitive data without users' knowledge. These hidden apps may either call home with the data, or pass it on to user-installed apps that have access to the network but no direct access to the data. This results in massive surveillance on which the user has absolutely no control.

-

2019-03

The MoviePass dis-service is planning to use face recognition to track people's eyes to make sure they won't put their phones down or look away during ads—and trackers.

-

2019-03

A study of 24 “health” apps found that 19 of them send sensitive personal data to third parties, which can use it for invasive advertising or discriminating against people in poor medical condition.

Whenever user “consent” is sought, it is buried in lengthy terms of service that are difficult to understand. In any case, “consent” is not sufficient to legitimize snooping.

-

2019-02

Facebook offered a convenient proprietary library for building mobile apps, which also sent personal data to Facebook. Lots of companies built apps that way and released them, apparently not realizing that all the personal data they collected would go to Facebook as well.

It shows that no one can trust a nonfree program, not even the developers of other nonfree programs.

-

2019-02

The AppCensus database gives information on how Android apps use and misuse users' personal data. As of March 2019, nearly 78,000 have been analyzed, of which 24,000 (31%) transmit the Advertising ID to other companies, and 18,000 (23% of the total) link this ID to hardware identifiers, so that users cannot escape tracking by resetting it.

Collecting hardware identifiers is in apparent violation of Google's policies. But it seems that Google wasn't aware of it, and, once informed, was in no hurry to take action. This proves that the policies of a development platform are ineffective at preventing nonfree software developers from including malware in their programs.

-

2019-02

Many nonfree apps have a surveillance feature for recording all the users' actions in interacting with the app.

-

2019-02

Twenty nine “beauty camera” apps that used to be on Google Play had one or more malicious functionalities, such as stealing users' photos instead of “beautifying” them, pushing unwanted and often malicious ads on users, and redirecting them to phishing sites that stole their credentials. Furthermore, the user interface of most of them was designed to make uninstallation difficult.

Users should of course uninstall these dangerous apps if they haven't yet, but they should also stay away from nonfree apps in general. All nonfree apps carry a potential risk because there is no easy way of knowing what they really do.

-

2019-02

An investigation of the 150 most popular gratis VPN apps in Google Play found that 25% fail to protect their users' privacy due to DNS leaks. In addition, 85% feature intrusive permissions or functions in their source code—often used for invasive advertising—that could potentially also be used to spy on users. Other technical flaws were found as well.

Moreover, a previous investigation had found that half of the top 10 gratis VPN apps have lousy privacy policies.

(It is unfortunate that these articles talk about “free apps.” These apps are gratis, but they are not free software.)

-

2019-01

The Weather Channel app stored users' locations to the company's server. The company is being sued, demanding that it notify the users of what it will do with the data.

We think that lawsuit is about a side issue. What the company does with the data is a secondary issue. The principal wrong here is that the company gets that data at all.

Other weather apps, including Accuweather and WeatherBug, are tracking people's locations.

-

2018-12

Around 40% of gratis Android apps report on the user's actions to Facebook.

Often they send the machine's “advertising ID,” so that Facebook can correlate the data it obtains from the same machine via various apps. Some of them send Facebook detailed information about the user's activities in the app; others only say that the user is using that app, but that alone is often quite informative.

This spying occurs regardless of whether the user has a Facebook account.

-

2018-10

Some Android apps track the phones of users that have deleted them.

-

2018-08

Some Google apps on Android record the user's location even when users disable “location tracking”.

There are other ways to turn off the other kinds of location tracking, but most users will be tricked by the misleading control.

-

2018-06

The Spanish football streaming app tracks the user's movements and listens through the microphone.

This makes them act as spies for licensing enforcement.

We expect it implements DRM, too—that there is no way to save a recording. But we can't be sure from the article.

If you learn to care much less about sports, you will benefit in many ways. This is one more.

-

2018-04

More than 50% of the 5,855 Android apps studied by researchers were found to snoop and collect information about its users. 40% of the apps were found to insecurely snitch on its users. Furthermore, they could detect only some methods of snooping, in these proprietary apps whose source code they cannot look at. The other apps might be snooping in other ways.

This is evidence that proprietary apps generally work against their users. To protect their privacy and freedom, Android users need to get rid of the proprietary software—both proprietary Android by switching to Replicant, and the proprietary apps by getting apps from the free software only F-Droid store that prominently warns the user if an app contains anti-features.

-

2018-04

Grindr collects information about which users are HIV-positive, then provides the information to companies.

Grindr should not have so much information about its users. It could be designed so that users communicate such info to each other but not to the server's database.

-

2018-03

The moviepass app and dis-service spy on users even more than users expected. It records where they travel before and after going to a movie.

Don't be tracked—pay cash!

-

2018-02

Spotify app harvests users' data to personally identify and know people through music, their mood, mindset, activities, and tastes. There are over 150 billion events logged daily on the program which contains users' data and personal information.

-

2017-11

Tracking software in popular Android apps is pervasive and sometimes very clever. Some trackers can follow a user's movements around a physical store by noticing WiFi networks.

-

2017-09

Instagram is forcing users to give away their phone numbers and won't let people continue using the app if they refuse.

-

2017-08

The Sarahah app uploads all phone numbers and email addresses in user's address book to developer's server.

(Note that this article misuses the words “free software” referring to zero price.)

-

2017-07

20 dishonest Android apps recorded phone calls and sent them and text messages and emails to snoopers.

Google did not intend to make these apps spy; on the contrary, it worked in various ways to prevent that, and deleted these apps after discovering what they did. So we cannot blame Google specifically for the snooping of these apps.

On the other hand, Google redistributes nonfree Android apps, and therefore shares in the responsibility for the injustice of their being nonfree. It also distributes its own nonfree apps, such as Google Play, which are malicious.

Could Google have done a better job of preventing apps from cheating? There is no systematic way for Google, or Android users, to inspect executable proprietary apps to see what they do.

Google could demand the source code for these apps, and study the source code somehow to determine whether they mistreat users in various ways. If it did a good job of this, it could more or less prevent such snooping, except when the app developers are clever enough to outsmart the checking.

But since Google itself develops malicious apps, we cannot trust Google to protect us. We must demand release of source code to the public, so we can depend on each other.

-

2017-05

Apps for BART snoop on users.

With free software apps, users could make sure that they don't snoop.

With proprietary apps, one can only hope that they don't.

-

2017-05

A study found 234 Android apps that track users by listening to ultrasound from beacons placed in stores or played by TV programs.

-

2017-04

Faceapp appears to do lots of surveillance, judging by how much access it demands to personal data in the device.

-

2017-04

Users are suing Bose for distributing a spyware app for its headphones. Specifically, the app would record the names of the audio files users listen to along with the headphone's unique serial number.

The suit accuses that this was done without the users' consent. If the fine print of the app said that users gave consent for this, would that make it acceptable? No way! It should be flat out illegal to design the app to snoop at all.

-

2017-04

Pairs of Android apps can collude to transmit users' personal data to servers. A study found tens of thousands of pairs that collude.

-

2017-03

Verizon announced an opt-in proprietary search app that it will pre-install on some of its phones. The app will give Verizon the same information about the users' searches that Google normally gets when they use its search engine.

Currently, the app is being pre-installed on only one phone, and the user must explicitly opt-in before the app takes effect. However, the app remains spyware—an “optional” piece of spyware is still spyware.

-

2017-01

The Meitu photo-editing app sends user data to a Chinese company.

-

2016-11

The Uber app tracks clients' movements before and after the ride.

This example illustrates how “getting the user's consent” for surveillance is inadequate as a protection against massive surveillance.

-

2016-11

A research paper that investigated the privacy and security of 283 Android VPN apps concluded that “in spite of the promises for privacy, security, and anonymity given by the majority of VPN apps—millions of users may be unawarely subject to poor security guarantees and abusive practices inflicted by VPN apps.”

Following is a non-exhaustive list, taken from the research paper, of some proprietary VPN apps that track users and infringe their privacy:

- SurfEasy

- Includes tracking libraries such as NativeX and Appflood, meant to track users and show them targeted ads.

- sFly Network Booster

- Requests the

READ_SMSandSEND_SMSpermissions upon installation, meaning it has full access to users' text messages. - DroidVPN and TigerVPN

- Requests the

READ_LOGSpermission to read logs for other apps and also core system logs. TigerVPN developers have confirmed this. - HideMyAss

- Sends traffic to LinkedIn. Also, it stores detailed logs and may turn them over to the UK government if requested.

- VPN Services HotspotShield

- Injects JavaScript code into the HTML pages returned to the users. The stated purpose of the JS injection is to display ads. Uses roughly five tracking libraries. Also, it redirects the user's traffic through valueclick.com (an advertising website).

- WiFi Protector VPN

- Injects JavaScript code into HTML pages, and also uses roughly five tracking libraries. Developers of this app have confirmed that the non-premium version of the app does JavaScript injection for tracking the user and displaying ads.

-

2016-09

Google's new voice messaging app logs all conversations.

-

2016-06

Facebook's new Magic Photo app scans your mobile phone's photo collections for known faces, and suggests you circulate the picture you take according to who is in the frame.

This spyware feature seems to require online access to some known-faces database, which means the pictures are likely to be sent across the wire to Facebook's servers and face-recognition algorithms.

If so, none of Facebook users' pictures are private anymore, even if the user didn't “upload” them to the service.

-

2016-05

Facebook's app listens all the time, to snoop on what people are listening to or watching. In addition, it may be analyzing people's conversations to serve them with targeted advertisements.

-

2016-04

A pregnancy test controller application not only can spy on many sorts of data in the phone, and in server accounts, it can alter them too.

-

2016-01

Apps that include Symphony surveillance software snoop on what radio and TV programs are playing nearby. Also on what users post on various sites such as Facebook, Google+ and Twitter.

-

2015-11

“Cryptic communication,” unrelated to the app's functionality, was found in the 500 most popular gratis Android apps.

The article should not have described these apps as “free”—they are not free software. The clear way to say “zero price” is “gratis.”

The article takes for granted that the usual analytics tools are legitimate, but is that valid? Software developers have no right to analyze what users are doing or how. “Analytics” tools that snoop are just as wrong as any other snooping.

-

2015-10

More than 73% and 47% of mobile applications, for Android and iOS respectively hand over personal, behavioral and location information of their users to third parties.

-

2015-08

Like most “music screaming” disservices, Spotify is based on proprietary malware (DRM and snooping). In August 2015 it demanded users submit to increased snooping, and some are starting to realize that it is nasty.

This article shows the twisted ways that they present snooping as a way to “serve” users better—never mind whether they want that. This is a typical example of the attitude of the proprietary software industry towards those they have subjugated.

Out, out, damned Spotify!

-

2015-07

Many retail businesses publish cr…apps that ask to spy on the user's own data—often many kinds.

Those companies know that snoop-phone usage trains people to say yes to almost any snooping.

-

2015-06

A study in 2015 found that 90% of the top-ranked gratis proprietary Android apps contained recognizable tracking libraries. For the paid proprietary apps, it was only 60%.

The article confusingly describes gratis apps as “free”, but most of them are not in fact free software. It also uses the ugly word “monetize”. A good replacement for that word is “exploit”; nearly always that will fit perfectly.

-

2015-05

Gratis Android apps (but not free software) connect to 100 tracking and advertising URLs, on the average.

-

2015-04

Widely used proprietary QR-code scanner apps snoop on the user. This is in addition to the snooping done by the phone company, and perhaps by the OS in the phone.

Don't be distracted by the question of whether the app developers get users to say “I agree”. That is no excuse for malware.

-

2014-11

Many proprietary apps for mobile devices report which other apps the user has installed. Twitter is doing this in a way that at least is visible and optional. Not as bad as what the others do.

-

2014-01

The Simeji keyboard is a smartphone version of Baidu's spying IME.

-

2013-12

The nonfree Snapchat app's principal purpose is to restrict the use of data on the user's computer, but it does surveillance too: it tries to get the user's list of other people's phone numbers.

-

2013-12

The Brightest Flashlight app sends user data, including geolocation, for use by companies.

The FTC criticized this app because it asked the user to approve sending personal data to the app developer but did not ask about sending it to other companies. This shows the weakness of the reject-it-if-you-dislike-snooping “solution” to surveillance: why should a flashlight app send any information to anyone? A free software flashlight app would not.

-

2012-12

FTC says most mobile apps for children don't respect privacy: https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2012/12/ftc-disclosures-severely-lacking-in-kids-mobile-appsand-its-getting-worse/.

Skype

(#SpywareInSkype)-

2019-08

Skype refuses to say whether it can eavesdrop on calls.

That almost certainly means it can do so.

-

2013-07

Skype contains spyware. Microsoft changed Skype specifically for spying.

Games

(#SpywareInGames)-

2020-10

Microsoft is imposing its surveillance on the game of Minecraft by requiring every player to open an account on Microsoft's network. Microsoft has bought the game and will merge all accounts into its network, which will give them access to people's data.

Minecraft players can play Minetest instead. The essential advantage of Minetest is that it is free software, meaning it respects the user's computer freedom. As a bonus, it offers more options.

-

2019-08

Microsoft recorded users of Xboxes and had human workers listen to the recordings.

Morally, we see no difference between having human workers listen and having speech-recognition systems listen. Both intrude on privacy.

-

2018-06

Red Shell is a spyware that is found in many proprietary games. It tracks data on users' computers and sends it to third parties.

-

2018-04

ArenaNet surreptitiously installed a spyware program along with an update to the massive multiplayer game Guild Wars 2. The spyware allowed ArenaNet to snoop on all open processes running on its user's computer.

-

2017-11

The driver for a certain gaming keyboard sends information to China.

-

2015-12

Many video game consoles snoop on their users and report to the internet—even what their users weigh.

A game console is a computer, and you can't trust a computer with a nonfree operating system.

-

2015-09

Modern gratis game cr…apps collect a wide range of data about their users and their users' friends and associates.

Even nastier, they do it through ad networks that merge the data collected by various cr…apps and sites made by different companies.

They use this data to manipulate people to buy things, and hunt for “whales” who can be led to spend a lot of money. They also use a back door to manipulate the game play for specific players.

While the article describes gratis games, games that cost money can use the same tactics.

-

2014-01

Angry Birds spies for companies, and the NSA takes advantage to spy through it too. Here's information on more spyware apps.

-

2005-10

Blizzard Warden is a hidden “cheating-prevention” program that spies on every process running on a gamer's computer and sniffs a good deal of personal data, including lots of activities which have nothing to do with cheating.

Spyware in Connected Equipment

(#SpywareInEquipment)-

2021-01

Most Internet connected devices in Mozilla's “Privacy Not Included” list are designed to snoop on users even if they meet Mozilla's “Minimum Security Standards.” Insecure design of the program running on some of these devices makes the user susceptible to be snooped on and exploited by crackers as well.

-

2019-12

As tech companies add microphones to a wide range of products, including refrigerators and motor vehicles, they also set up transcription farms where human employees listen to what people say and tweak the recognition algorithms.

-

2017-08

The bad security in many Internet of Stings devices allows ISPs to snoop on the people that use them.

Don't be a sucker—reject all the stings.

(It is unfortunate that the article uses the term “monetize”.)

TV Sets

(#SpywareInTVSets)Emo Phillips made a joke: The other day a woman came up to me and said, “Didn't I see you on television?” I said, “I don't know. You can't see out the other way.” Evidently that was before Amazon “smart” TVs.

-

2022-04

Today's “smart” TVs push people to surrender to tracking via internet. Some won't work unless they have a chance to download nonfree software. And they are designed for programmed obsolescence.

-

2022-01

“Smart” TV manufacturers spy on people using various methods, and harvest their data. They are collecting audio, video, and TV usage data to profile people.

-

2020-10

TV manufacturers are turning to produce only “Smart” TV sets (which include spyware) that it's now very hard to find a TV that doesn't spy on you.

It appears that those manufacturers business model is not to produce TV and sell them for money, but to collect your personal data and (possibly) hand over them to others for benefit.

-

2020-06

TV manufacturers are able to snoop every second of what the user is watching. This is illegal due to the Video Privacy Protection Act of 1988, but they're circumventing it through EULAs.

-

2019-01

Vizio TVs collect “whatever the TV sees,” in the own words of the company's CTO, and this data is sold to third parties. This is in return for “better service” (meaning more intrusive ads?) and slightly lower retail prices.

What is supposed to make this spying acceptable, according to him, is that it is opt-in in newer models. But since the Vizio software is nonfree, we don't know what is actually happening behind the scenes, and there is no guarantee that all future updates will leave the settings unchanged.

If you already own a Vizio “smart” TV (or any “smart” TV, for that matter), the easiest way to make sure it isn't spying on you is to disconnect it from the Internet, and use a terrestrial antenna instead. Unfortunately, this is not always possible. Another option, if you are technically oriented, is to get your own router (which can be an old computer running completely free software), and set up a firewall to block connections to Vizio's servers. Or, as a last resort, you can replace your TV with another model.

-

2018-04

Some “Smart” TVs automatically load downgrades that install a surveillance app.

We link to the article for the facts it presents. It is too bad that the article finishes by advocating the moral weakness of surrendering to Netflix. The Netflix app is malware too.

-

2017-02

Vizio “smart” TVs report everything that is viewed on them, and not just broadcasts and cable. Even if the image is coming from the user's own computer, the TV reports what it is. The existence of a way to disable the surveillance, even if it were not hidden as it was in these TVs, does not legitimize the surveillance.

-

2015-11

Some web and TV advertisements play inaudible sounds to be picked up by proprietary malware running on other devices in range so as to determine that they are nearby. Once your Internet devices are paired with your TV, advertisers can correlate ads with Web activity, and other cross-device tracking.

-

2015-11

Vizio goes a step further than other TV manufacturers in spying on their users: their “smart” TVs analyze your viewing habits in detail and link them your IP address so that advertisers can track you across devices.

It is possible to turn this off, but having it enabled by default is an injustice already.

-

2015-11

Tivo's alliance with Viacom adds 2.3 million households to the 600 millions social media profiles the company already monitors. Tivo customers are unaware they're being watched by advertisers. By combining TV viewing information with online social media participation, Tivo can now correlate TV advertisement with online purchases, exposing all users to new combined surveillance by default.

-

2015-07

Vizio “smart” TVs recognize and track what people are watching, even if it isn't a TV channel.

-

2015-05

Verizon cable TV snoops on what programs people watch, and even what they wanted to record.

-

2015-04

Vizio used a firmware “upgrade” to make its TVs snoop on what users watch. The TVs did not do that when first sold.

-

2015-02

The Samsung “Smart” TV transmits users' voice on the internet to another company, Nuance. Nuance can save it and would then have to give it to the US or some other government.

Speech recognition is not to be trusted unless it is done by free software in your own computer.

In its privacy policy, Samsung explicitly confirms that voice data containing sensitive information will be transmitted to third parties.

-

2014-11

The Amazon “Smart” TV is snooping all the time.

-

2014-09

More or less all “smart” TVs spy on their users.

The report was as of 2014, but we don't expect this has got better.

This shows that laws requiring products to get users' formal consent before collecting personal data are totally inadequate. And what happens if a user declines consent? Probably the TV will say, “Without your consent to tracking, the TV will not work.”

Proper laws would say that TVs are not allowed to report what the user watches—no exceptions!

-

2014-05

LG disabled network features on previously purchased “smart” TVs, unless the purchasers agreed to let LG begin to snoop on them and distribute their personal data.

-

2014-05

Spyware in LG “smart” TVs reports what the user watches, and the switch to turn this off has no effect. (The fact that the transmission reports a 404 error really means nothing; the server could save that data anyway.)

Even worse, it snoops on other devices on the user's local network.

LG later said it had installed a patch to stop this, but any product could spy this way.

Meanwhile, LG TVs do lots of spying anyway.

-

2013-11

Spyware in LG “smart” TVs reports what the user watches, and the switch to turn this off has no effect. (The fact that the transmission reports a 404 error really means nothing; the server could save that data anyway.)

Even worse, it snoops on other devices on the user's local network.

LG later said it had installed a patch to stop this, but any product could spy this way.

-

2012-12

Crackers found a way to break security on a “smart” TV and use its camera to watch the people who are watching TV.

Cameras

(#SpywareInCameras)-

2023-12

Surveillance cameras put in by government A to surveil for it may be surveilling for government B as well. That's because A put in a product made by B with nonfree software.

(Please note that this article misuses the word “hack” to mean “break security.”)

-

2023-07

Driverless cars in San Francisco collect videos constantly, using cameras inside and outside, and governments have already collected those videos secretly.

As the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project says, they are “driving us straight into authoritarianism.” We must regulate all cameras that collect images that can be used to track people, to make sure they are not used for that.

-

2019-02

The Ring doorbell camera is designed so that the manufacturer (now Amazon) can watch all the time. Now it turns out that anyone else can also watch, and fake videos too.

The third party vulnerability is presumably unintentional and Amazon will probably fix it. However, we do not expect Amazon to change the design that allows Amazon to watch.

-

2019-01

Amazon Ring “security” devices send the video they capture to Amazon servers, which save it long-term.

In many cases, the video shows everyone that comes near, or merely passes by, the user's front door.

The article focuses on how Ring used to let individual employees look at the videos freely. It appears Amazon has tried to prevent that secondary abuse, but the primary abuse—that Amazon gets the video—Amazon expects society to surrender to.

-

2018-10

Nearly all “home security cameras” give the manufacturer an unencrypted copy of everything they see. “Home insecurity camera” would be a better name!

When Consumer Reports tested them, it suggested that these manufacturers promise not to look at what's in the videos. That's not security for your home. Security means making sure they don't get to see through your camera.

-

2017-10

Every “home security” camera, if its manufacturer can communicate with it, is a surveillance device. Canary camera is an example.

The article describes wrongdoing by the manufacturer, based on the fact that the device is tethered to a server.

More about proprietary tethering.

But it also demonstrates that the device gives the company surveillance capability.

-

2016-03

Over 70 brands of network-connected surveillance cameras have security bugs that allow anyone to watch through them.

-

2015-11

The Nest Cam “smart” camera is always watching, even when the “owner” switches it “off.”

A “smart” device means the manufacturer is using it to outsmart you.

Toys

(#SpywareInToys)-

2017-11

The Furby Connect has a universal back door. If the product as shipped doesn't act as a listening device, remote changes to the code could surely convert it into one.

-

2017-11

A remote-control sex toy was found to make audio recordings of the conversation between two users.

-

2017-03

A computerized vibrator was snooping on its users through the proprietary control app.

The app was reporting the temperature of the vibrator minute by minute (thus, indirectly, whether it was surrounded by a person's body), as well as the vibration frequency.

Note the totally inadequate proposed response: a labeling standard with which manufacturers would make statements about their products, rather than free software which users could have checked and changed.

The company that made the vibrator was sued for collecting lots of personal information about how people used it.

The company's statement that it was anonymizing the data may be true, but it doesn't really matter. If it had sold the data to a data broker, the data broker would have been able to figure out who the user was.

Following this lawsuit, the company has been ordered to pay a total of C$4m to its customers.

-

2017-02

“CloudPets” toys with microphones leak childrens' conversations to the manufacturer. Guess what? Crackers found a way to access the data collected by the manufacturer's snooping.

That the manufacturer and the FBI could listen to these conversations was unacceptable by itself.

-

2016-12

The “smart” toys My Friend Cayla and i-Que can be remotely controlled with a mobile phone; physical access is not necessary. This would enable crackers to listen in on a child's conversations, and even speak into the toys themselves.

This means a burglar could speak into the toys and ask the child to unlock the front door while Mommy's not looking.

-

2016-12

The “smart” toys My Friend Cayla and i-Que transmit children's conversations to Nuance Communications, a speech recognition company based in the U.S.

Those toys also contain major security vulnerabilities; crackers can remotely control the toys with a mobile phone. This would enable crackers to listen in on a child's speech, and even speak into the toys themselves.

- 2015-02

Drones

(#SpywareInDrones)-

2017-08

While you're using a DJI drone to snoop on other people, DJI is in many cases snooping on you.

Other Appliances

(#SpywareAtHome)-

2023-09

Philips Hue, the most ubiquitous home automation product in the US, is planning to soon force users to log in to the app server in order to be able to adjust a lightbulb, or use other functionalities, in what amounts to a massive user-tracking data grab.

-

2020-09

Many employers are using nonfree software, including videoconference software, to surveil and monitor staff working at home. If the program reports whether you are “active,” that is in effect a malicious surveillance feature.

-

2020-08

Google Nest is taking over ADT. Google sent out a software update to its speaker devices using their back door that listens for things like smoke alarms and then notifies your phone that an alarm is happening. This means the devices now listen for more than just their wake words. Google says the software update was sent out prematurely and on accident and Google was planning on disclosing this new feature and offering it to customers who pay for it.

-

2020-06

“Bossware” is malware that bosses coerce workers into installing in their own computers, so the bosses can spy on them.

This shows why requiring the user's “consent” is not an adequate basis for protecting digital privacy. The boss can coerce most workers into consenting to almost anything, even probable exposure to contagious disease that can be fatal. Software like this should be illegal and bosses that demand it should be prosecuted for it.

-

2019-07

Google “Assistant” records users' conversations even when it is not supposed to listen. Thus, when one of Google's subcontractors discloses a thousand confidential voice recordings, users were easily identified from these recordings.

Since Google “Assistant” uses proprietary software, there is no way to see or control what it records or sends.

Rather than trying to better control the use of recordings, Google should not record or listen to the person's voice. It should only get commands that the user wants to send to some Google service.

-

2019-05

Amazon Alexa collects a lot more information from users than is necessary for correct functioning (time, location, recordings made without a legitimate prompt), and sends it to Amazon's servers, which store it indefinitely. Even worse, Amazon forwards it to third-party companies. Thus, even if users request deletion of their data from Amazon's servers, the data remain on other servers, where they can be accessed by advertising companies and government agencies. In other words, deleting the collected information doesn't cancel the wrong of collecting it.

Data collected by devices such as the Nest thermostat, the Philips Hue-connected lights, the Chamberlain MyQ garage opener and the Sonos speakers are likewise stored longer than necessary on the servers the devices are tethered to. Moreover, they are made available to Alexa. As a result, Amazon has a very precise picture of users' life at home, not only in the present, but in the past (and, who knows, in the future too?)

-

2019-04

Some of users' commands to the Alexa service are recorded for Amazon employees to listen to. The Google and Apple voice assistants do similar things.

A fraction of the Alexa service staff even has access to location and other personal data.

Since the client program is nonfree, and data processing is done “in the cloud” (a soothing way of saying “We won't tell you how and where it's done”), users have no way to know what happens to the recordings unless human eavesdroppers break their non-disclosure agreements.

-

2019-02

The HP “ink subscription” cartridges have DRM that constantly communicates with HP servers to make sure the user is still paying for the subscription, and hasn't printed more pages than were paid for.

Even though the ink subscription program may be cheaper in some specific cases, it spies on users, and involves totally unacceptable restrictions in the use of ink cartridges that would otherwise be in working order.

-

2018-08

Crackers found a way to break the security of an Amazon device, and turn it into a listening device for them.

It was very difficult for them to do this. The job would be much easier for Amazon. And if some government such as China or the US told Amazon to do this, or cease to sell the product in that country, do you think Amazon would have the moral fiber to say no?

(These crackers are probably hackers too, but please don't use “hacking” to mean “breaking security”.)

-

2018-04

A medical insurance company offers a gratis electronic toothbrush that snoops on its user by sending usage data back over the Internet.

-

2017-08

Sonos told all its customers, “Agree” to snooping or the product will stop working. Another article says they won't forcibly change the software, but people won't be able to get any upgrades and eventually it will stop working.

-

2017-06

Lots of “smart” products are designed to listen to everyone in the house, all the time.

Today's technological practice does not include any way of making a device that can obey your voice commands without potentially spying on you. Even if it is air-gapped, it could be saving up records about you for later examination.

-

2014-07

Nest thermometers send a lot of data about the user.

-

2013-10

Rent-to-own computers were programmed to spy on their renters.

Wearables

(#SpywareOnWearables)-

2018-07

Tommy Hilfiger clothing will monitor how often people wear it.

This will teach the sheeple to find it normal that companies monitor every aspect of what they do.

“Smart” Watches

-

2020-09

Internet-enabled watches with proprietary software are malware, violating people (specially children's) privacy. In addition, they have a lot of security flaws. They permit security breakers (and unauthorized people) to access the watch.

Thus, ill-intentioned unauthorized people can intercept communications between parent and child and spoof messages to and from the watch, possibly endangering the child.

(Note that this article misuses the word “hackers” to mean “crackers.”)

-

2016-03

A very cheap “smart watch” comes with an Android app that connects to an unidentified site in China.

The article says this is a back door, but that could be a misunderstanding. However, it is certainly surveillance, at least.

-

2014-07

An LG “smart” watch is designed to report its location to someone else and to transmit conversations too.

Vehicles

(#SpywareInVehicles)-

2024-09

Kia cars were built with a back door that enabled the company's server to locate them and take control of them. The car owner had access to these controls through the Kia server. That the car owner had such control is not objectionable. However, that Kia itself had such control is Orwellian, and ought to be illegal. The icing on the Orwellian cake is that the server had a security fault which allowed absolutely anyone to activate those controls for any Kia car.

Many people will be outraged at that security bug, but this was presumably an accident. The fact that Kia had such control over cars after selling them to customers is what outrages us, and that must have been intentional on Kia's part.

-

2024-03

GM is spying on drivers who own or rent their cars, and give away detailed driving data to insurance companies through data brokers. These companies then analyze the data, and hike up insurance prices if they think the data denotes “risky driving.” For the car to make this data available to anyone but the owner or renter of the car should be a crime. If the car is owned by a rental company, that company should not have access to it either.

-

2023-11

Recent autos offer a feature by which the drivers can connect their snoop-phones to the car. That feature snoops on the calls and texts and gives the data to the car manufacturer, and to the state.

A good privacy law would prohibit cars recording this data about the users' activities. But not just this data—lots of other data too.

-

2023-09

In an article from Mozilla, every car brand they researched has failed their privacy tests. Some car manufacturers explicitly mention that they collect data which includes “sexual activities” and “genetic information”. Not only collecting any of such data is a huge privacy violation in the first place, some companies assume drivers and passengers' consent before they get in the car. Notably, Tesla threatens that the car may be “inoperable” if the user opts out of data collection.

-

2023-04

Tesla cars record videos of activity inside the car, and company staff can watch those recordings and copy them. Or at least they were able to do so until last year.

Tesla may have changed some security functions so that this is harder to do. But if Tesla can get those recordings, that is because it is planning for some people to use them in some situation, and that is unjust already. It should be illegal to make a car that takes photos or videos of the people in the car—or of people outside the car.

-

2023-04

GM is switching to a new audio/video system in its cars in order to collect complete information about what people in the car watch or listen to, and also how they drive.

The new system for navigation and “driving assistance” will be tethered to various online dis-services, and GM will snoop on everything the users do with them. But don't feel bad about that, because some of these subscriptions will be gratis for the first 8 years.

-

2023-02

Volkswagen tracks the location of every driver, and sells that data to third-parties. However, it refuses to use the data to implement a feature for the benefit of its customers unless they pay extra money for it.

This came to attention and brought controversy when Volkswagen refused to locate a car-jacked vehicle with a toddler in it because the owner of the car had not subscribed to the relevant service.

-

2021-05

Ford is planning to force ads on drivers in cars, with the ability for the owner to pay extra to turn them off. The system probably imposes surveillance on drivers too.

-

2020-08

New Toyotas will upload data to AWS to help create custom insurance premiums based on driver behaviour.

Before you buy a “connected” car, make sure you can disconnect its cellular antenna and its GPS antenna. If you want GPS navigation, get a separate navigator which runs free software and works with Open Street Map.

-

2019-12

Most modern cars now record and send various kinds of data to the manufacturer. For the user, access to the data is nearly impossible, as it involves cracking the car's computer, which is always hidden and running with proprietary software.

-

2019-03

Tesla cars collect lots of personal data, and when they go to a junkyard the driver's personal data goes with them.

-

2019-02

The FordPass Connect feature of some Ford vehicles has near-complete access to the internal car network. It is constantly connected to the cellular phone network and sends Ford a lot of data, including car location. This feature operates even when the ignition key is removed, and users report that they can't disable it.

If you own one of these cars, have you succeeded in breaking the connectivity by disconnecting the cellular modem, or wrapping the antenna in aluminum foil?

-

2018-11

In China, it is mandatory for electric cars to be equipped with a terminal that transfers technical data, including car location, to a government-run platform. In practice, manufacturers collect this data as part of their own spying, then forward it to the government-run platform.

-

2018-10

GM tracked the choices of radio programs in its “connected” cars, minute by minute.

GM did not get users' consent, but it could have got that easily by sneaking it into the contract that users sign for some digital service or other. A requirement for consent is effectively no protection.

The cars can also collect lots of other data: listening to you, watching you, following your movements, tracking passengers' cell phones. All such data collection should be forbidden.